Writing on the wall

In the tiniest of thumbnail sketches, the essayist William H. Gass described Arabic as having the enduring ability “to look good in anything it puts on.”[1] He continued:

“A line of the Qur’an can embellish a Moorish wall even for eyes that understand nothing of what it says.”

One is hard-pressed to disagree.

Though it lies thousands of kilometers distant in space and is even more removed in time from al-Andalus or any “Moorish wall,” the tiled façade of the seventh-century Dome of the Rock offers a fit example of Arabic’s decorative finery.

A façade view of the Dome of the Rock, via Creative Commons

The eldritch power to enchant by orthographic feint belongs not only to the language of the Qur’an, but to Arabic script no matter how banal in content. This is true even of corporate design, normally the province of good ideas ground by committee to unpalatable mush.

Consider the teardrop glyph employed by the Doha-based broadcaster Al-Jazeera. It consists of nothing more than the company’s name, padded and massaged into the familiar golden tulip that buds suggestively on lower-thirds across the Arabic-speaking world. (Click here for an animation of plain text transforming into the logo above.)

* * *

Across the globe Arabic of one kind of another serves as the language of daily life for hundreds of millions, among whom are Arabs and non-Arabs alike; Jews, Christians, and atheists, as well as Alawis, Bahais, Druze, and others.[2] It is Islam, however, that most animated Arabic’s development, ensured its diffusion beyond the Hijaz, and most profoundly shaped the cultural institutions that became the flat stone surfaces of its many deep-hewn expressions.

As Tarif Khalidi declared in his “interpretation” (i.e. translation) of Islam’s scripture, “the Qur’an is the axial text of a major religious civilization and of a major world language.” Whatever purchase other traditions have over the language, Arabic remains in some real sense inseparable from Islam.[3]

Islam did not become the majority religion of the diverse peoples living under putatively Muslim rule until hundreds of years after the death of Muhammad (c. 632), yet the civilizational efflorescence that followed the Islamic conquests saw the language employed in new offices. Monumental architecture, public works, art, and like expressions all grew to fill the space opened by the continued evolution of the faith.

Among the signal features of the new order was the generally subscribed[4] prohibition against pictorial depictions of living creatures, a measure that ensured the primacy of the word and prevented iconography and idolatry from taking root.

In the place of human or animal forms, the language itself padded margins and enlivened façades. Whereas pre-Islamic Arabia and Western Christendom tended to draw on the great funds of religious storytelling and folklore for their graphic adornment, the walls and pages of Dar al-Islam were instead bedecked in repeating patterns, in geometric abstractions, and in the immaculate word.

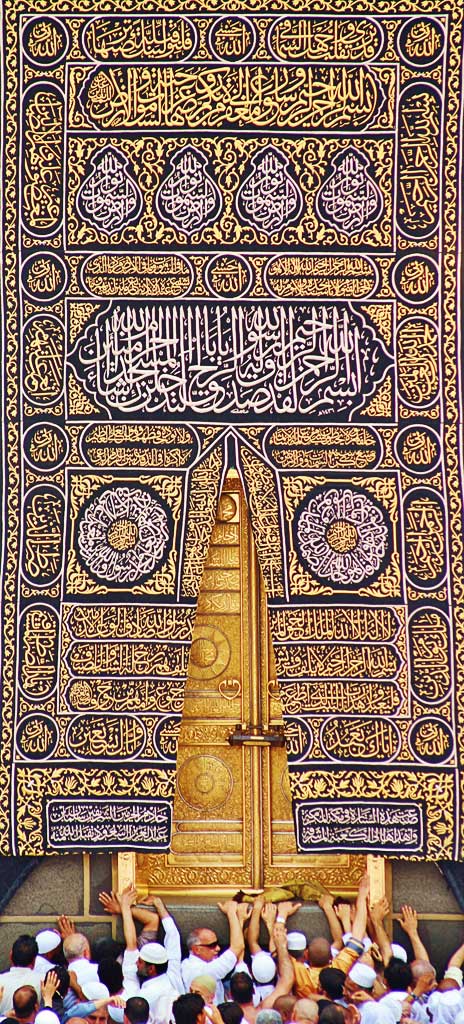

The Kiswa, Creative Commons

In a particularly ornate work it might suffice that a few recognizable lines of an inscription would recall to mind a long-memorized Qur’anic verse that would be, for all practical purposes, unreadable where it adorned mosque walls or palace diwans. The passerby could trust, however, that the inscrutable words that scrolled onward would surely carry him through to verse’s end and deposit him safely on familiar ground – if only he took the time to study them with devotion and earnestness.

Whatever its deployment, Arabic retains an evanescent beauty that is not liable to burn off under scrutiny. Too much time spent surgically extracting discernable text from a calligraphic thicket may distract from holistic appreciation, but such works are not mere arabesque to be admired in shape and form without apprehension of content, provenance, or meaning. However beautiful a Moorish wall – and such a wall does have a beauty accessible even to the uninitiated – the subtler grace most worthy of memorial is found almost always in the words themselves.

[1] William H. Gass, “Not about the money” in Lapham’s Quarterly (2009), available: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/eros/not-about-money.

[2] “World Arabic Language Day 2017,” UNESCO, available: https://en.unesco.org/world-arabic-language-day.

[3] Tarif Khalidi, trans. The Qur’an (Viking, 2008), ix-xix.

[4] “Figural representation in Islamic art,” The Met, available: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/figs/hd_figs.htm.