Woven air

Advantages of wearing Muslin Dresses! ___ dedicated to the serious attention of the Fashionable Ladies of Great Britain (1802) // Creative Commons

In his axiomatic thirteenth-century travel account, Marco Polo speaks of Mosul as a city of sumptuary fineness and an epicenter of global cloth production: “All the cloths of gold and silk that are called Mosolins are made in this country; and those great Merchants called Mosolins, who carry for sale such quantities of spicery and pearls and cloths of silk and gold, are also from this kingdom.”

Garbled transliteration notwithstanding, Mosul did lend its name to the fine cloth that Europeans associated with the city: muslin. And what a cloth it was. In the thirteenth century, Europeans hadn’t yet grasped how to comb and card cotton fibers, or to spin and weave them into a fine plain-woven cloth. As a result, fine muslin imported from the east was prized by royalty and upwardly mobile elites. Today, muslin is a byword for cheap canvas used in theatrical staging, but in Polo’s time, it was the stuff of high-street luxury.

Marie Antoinette, as depicted in her infamous muslin dress, which ignited a fashion trend and earned the reproach of polite society as being little better than chambermaids’ rags. // Creative Commons

Nonetheless, Polo’s account of the cloth warrants scrutiny. Most obviously, “The Travels of Marco Polo” should be held at arm’s length because it wasn’t actually written by the Venetian merchant traveler himself. Rather, the account was put to paper by an Arthurian romance writer named Rustichello da Pisa, who absorbed the narrative while sharing a prison cell with Polo. This transmission took place not during Polo’s 24 years of wandering, but upon the traveler’s return to Italy, where he was jailed by the rival Genoese.[1] The account is wrong about Mosul and muslin, too. Mesopotamian cities did play a pivotal role in the cloth trade, yet the diaphanous fabric described in Polo’s account was manufactured not in Mosul, but further east, in modern-day India and Bangladesh.

Without doubt, the English language is a storehouse of sartorial terms imported from the world of classical Islam: damask (a Damascene cloth variously of silk, linen, or wool) and fustian (a cloth made in Fustat, precursor to medieval Cairo) among them. Yet from the renaissance well into the modern period, the Indian subcontinent was far and away the dynamo of global cloth production.

In this sense, the Anglophone world’s greatest linguistic debt is doubtless owed to the genius of the latter’s textile industry: pajama, calico, gingham, khaki, madras, dungaree, chintz, and a great many other English words are, like the goods they describe, imports from the later Mughal empire. In the period of Britain’s entree into global trade, the predominance of the Mughals is difficult to overstate. Bengali craftsmen were pioneering master weavers, and they excelled in wood-blocking and color-fast dyeing to such a degree that their high-tech industries served as the boiler room of a Mughal empire that by 1600 accounted for a staggering one-quarter of global industry.[2]

Yet as industrial history, the production of Bengali muslin is almost absurdly precious.[3] Among the cotton plants that grew exclusively in the Meghna River basin, only the finest fibers — which were unique in their tendency to contract and grow stronger when waterlogged — were suited for production of the ethereal muslin demanded by discerning royalty. Using the razor-toothed jawbone of a river catfish, carders could separate the finer fibers of the harvest. Then, and only in oppressively humid conditions by first and last light, could nimble-fingered women (and only women) spin the fibers into thread, strumming them with a special bow to raise up and pluck the finest tufts. Finally, the threads were woven into cloth.

The result possessed an otherworldly fineness. It was said that a bolt of muslin could be passed through a signet ring. The preeminence of Bengali cloth production was noted by Roman writers as early as the first century, a tendency which lent muslin it most poetic and alluring name: baft hawa, literally: woven air.

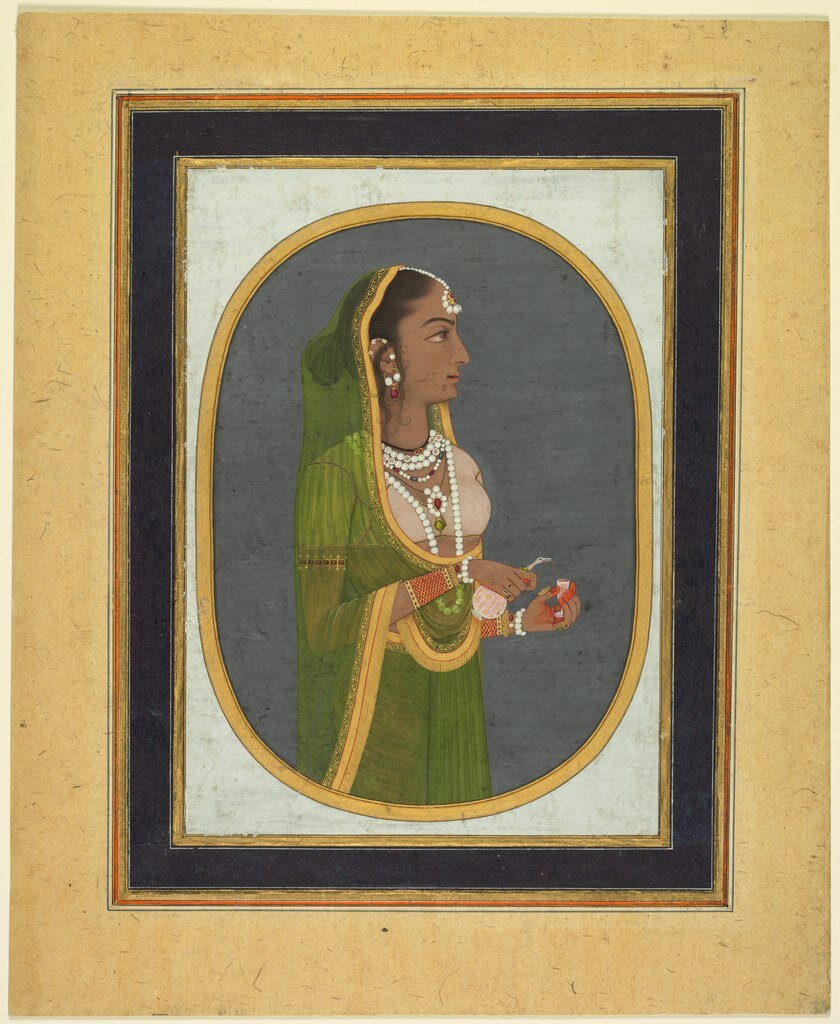

“Court Lady Pouring Wine” attributed to Muhammad Rizavi Hindi 18th century // Cleveland Museum of Art via Creative Commons

Remarking on muslin’s gossamer lightness, the Roman writer Petronius noted: “Thy bride might as well clothe herself with a garment of the wind as stand forth publicly naked under her clouds of muslin.”[4]

For the Persianate Mughals — for a time, at least — that was precisely the point. These luxuriously sheer fabrics displayed both the wearer’s body and wealth, gratifying the sensual imperative to reveal while concealing.

The industrial production of Bengali muslin withered under the East India Company. Today, only a small industry — largely producing patterned muslins and purpose-woven garments — remains.[5] The tense relationship between concealing and revealing and attraction, however, remains as relevant as ever.

This tension is alive in the verse of Zeb-Un-Nissa, seventeenth-century poet, princess, and Quranic exegete; though her dress was noted as being “simple and austere,” Zeb-Un-Nissa’s erotic poetry (ghazal) was fully cognizant of the tension inherent to the form.

I will not lift my veil,—

For, if I did, who knows?

The bulbul might forget the rose,

The Brahman worshipper

Adoring Lakshmi’s grace

Might turn, forsaking her,

To see my face;

My beauty might prevail.

Think how within the flower

Hidden as in a bower

Her fragrant soul must be,

And none can look on it;

So me the world can see

Only within the verses I have writ—

I will not lift the veil.[6]

[1] In this sense, Polo’s account resembles that of Ibn Battuta, in that it was the product of an amanuensis and sometimes collaborator.

[2] W. Dalrymple, The Anarchy: the East India Company, corporate violence, and the pillage of an empire (London, 2019), 14.

[3] The Metropolitan Museum, “Bangladeshi Islamic Art,” available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/ruminations/2015/bangladeshi-islamic-art.

[4] Petronius, Satyricon, available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0972.phi001.perseus-eng1:55.

[5] UNESCO, “The Traditional Art of Jamdani Weaving,” available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/traditional-art-of-jamdani-weaving-00879.

[6] M. Lal and J. Westbrook, trans. The Diwan of Zeb-Un-Nissa (London, 1913), 12.